by bil2016 | Feb 28, 2019 | FAQ, Legal Articles & Tips

Prior to retaining a lawyer in a personal injury case, you would be wise to ask about how you will be expected to pay the lawyer. Usually, personal injury lawyers will charge on a contingency fee basis; meaning the lawyer will charge a percentage of the amounts...

by Barbara Webster-Evans | Mar 15, 2018 | Legal Articles & Tips, News & Research

Over the years many of our clients have suffered head injuries while cycling, riding motorcycles or longboards, skiing or skating. We strongly recommend that everyone who could possibly benefit from wearing an approved helmet while engaging in sporting activities...

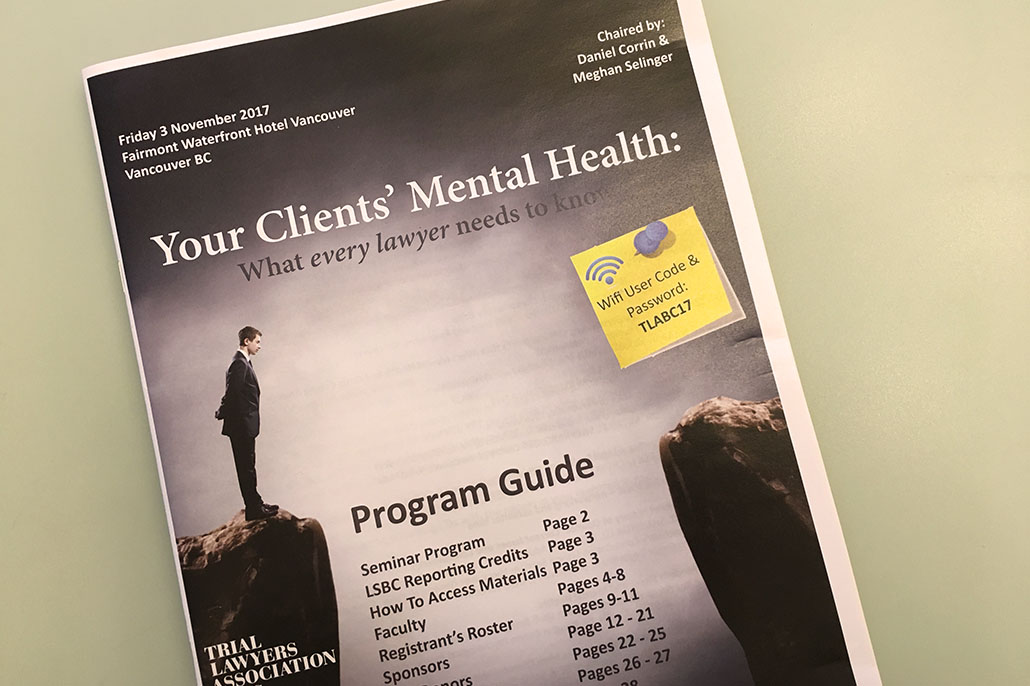

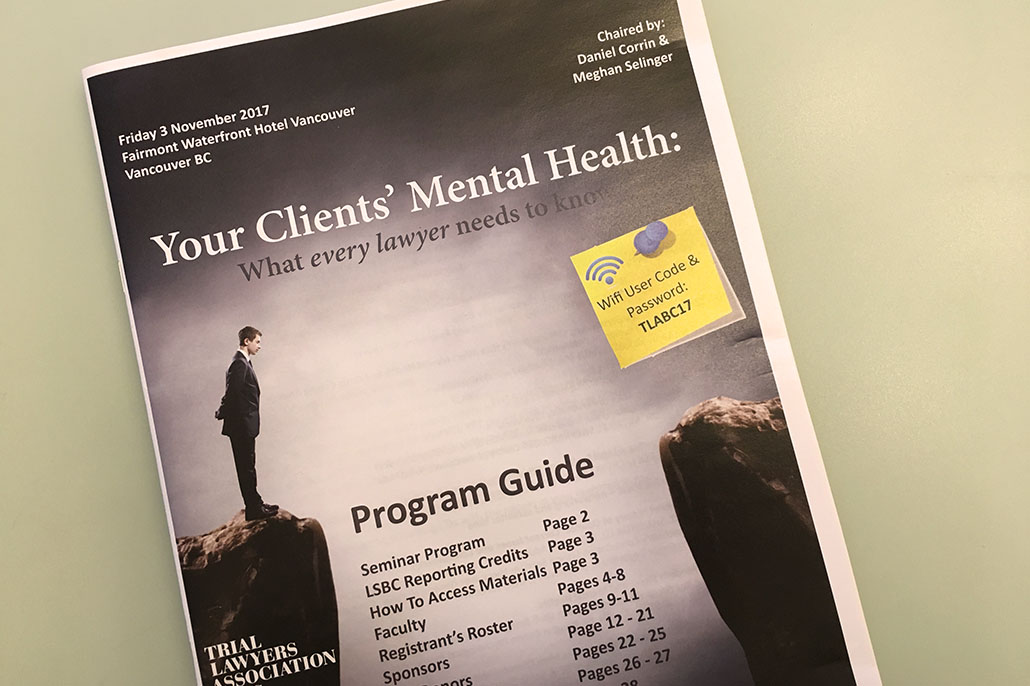

by Daniel Corrin | Dec 18, 2017 | Community Events & Programs, Legal Articles & Tips

On November 3rd, 2017, we appreciated the input by various specialist professionals, as Dan Corrin co-chaired this information-rich session on how to deal with mental illness in litigation; Your Client’s Mental Health: What every lawyer needs to know. The conference,...

by bil2016 | May 12, 2015 | ICBC Cases, Legal Articles & Tips

This week, the Court of Appeal for British Columbia released reasons regarding an appeal from an order from the BC Supreme Court, which concerned whether or not out-of-pocket interest payments incurred to finance disbursements are recoverable as disbursements....

by bil2016 | Oct 9, 2014 | Legal Articles & Tips

In the case of Symons v. Insurance Corporation of British Columbia 2014 BCSC 1883, a summary trial application, the Court considered the “revival” of ICBC disability benefits following the Plaintiff’s attempt to return to work. In reasons for judgment, released today,...

by bil2016 | Oct 3, 2014 | Legal Articles & Tips

The case of Maras v. Seemore Entertainment Ltd., 2013 BCSC 1842, involved a Plaintiff who was assaulted outside a Downtown Vancouver nightclub. Liability for the incident was shared by the corporate Defendant, which owned the nightclub, and three of the club’s...